TRBQ paid a visit to the United House of Prayer for All People in Harlem to spend some time with a gospel brass band called the McCullough Sons of Thunder. And we talked with some neuroscientists who study our perceptions of music.

When the McCullough Sons of Thunder play at the United House of Prayer for All People, you feel it.

“We play this music from our souls, sweating,” says band director Elder Edward Babb. “Tie is wet, shirt is wet, even my socks are wet. And so we give our body, our soul and our spirit to render this music.”

The Sons of Thunder rehearse in a small meeting room. The ceiling is low, the lights are fluorescent—and none of that matters. The moment they start playing, the room is filled with the electricity of their music, and their movement.

One player has just come from his job working for the MTA, and he has to change out of his uniform. He is especially on fire, dancing ecstatically while the band plays.

The band of a dozen or so men was organized 52 years ago.

“I was 17 going on 18 at the time,” says Elder Babb. “We’re still there. Our sousaphone player, the ripe age of 84. Our bass drum beater wasn’t here tonight, but he’ll be 95 this year.”

The six of them who compose the band’s “nucleus,” as Babb calls it, have been there for all 52 years.

The thunderous power of this band highlights how music can move the listener—physically and emotionally. We felt shivers when they played.

Psyche Loui, a neuroscience researcher at Wesleyan University, calls this sensation “chills.”

“Goose bumps or goose flesh or skin orgasms,” she says. “Those are all sort of terms that have been used to define chills. But in our experiments, it has to do with an intense aesthetic experience that people get when they are perceiving some art that’s really subjectively kind of emotional.”

In other words, she says, it’s an emotional response that becomes physical.

Psyche Loui does research into other areas of music psychology, beyond chills. She’s interested in music perception and cognition. That means she studies why some people can’t sing and some can.

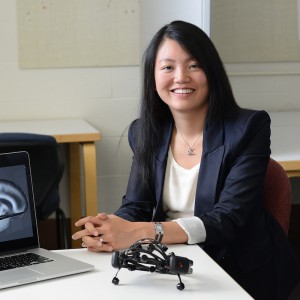

Wesleyan University psychologist Psyche Loui investigates how music can give us “chills.” (Photo: Olivia Drake/Wesleyan University)

“That has led me down a path of looking at individual differences in music,” she says.

One obvious difference in people’s perception of music is in preference and taste.

“There are some people who will really, honestly say that some pieces of music like Justin Bieber are really, really, really moving to them,” she says. “And then there will be some people who say, ‘There’s something about a Rachmaninoff piano concerto that’s really doing it for me.’”

Just as there are differences in taste, Loui says there are also differences in the extent to which music affects people.

“A lot of people will report that they do get these strong emotional responses to music,” she says. “And then on the other hand, there are people who never seem to respond to music emotionally.”

Loui says her most interesting findings have to do with the structural differences in the brains of those two groups—the unmoved group and the “chill” group.

The brains of people in the chill group, she says, have a stronger connection between the auditory areas and the emotion-processing areas.

Psyche Loui is not the only researcher who is interested in how music puts us in a state of mind that is best described with hypercolloquial terms. Petr Janata at the University of California at Davis is interested in how we “groove” to music.

His definition of groove: “It’s the pleasurable urge to move that’s elicited by music.”

Neuroscientist Petr Janata studies how music, motion and emotions map in the brain. (Photo: Karin Higgins/UC Davis)

But for Janata, it goes deeper than that.

“I believe a similarly important part of the definition is this sense of unity that people feel with the music or people who they’re engaged in the music with,” he says.

Janata says sometimes it’s hard for people to take his study of “groove” seriously.

“It generally conjures up associations of bad hair and bad clothes from the ’70s,” he says. “I think whenever you take a term from folk culture, and then try to establish that as a scientific concept that one can study rigorously, it meets with some raised eyebrows.”

He says he’s not so much about the word itself.

“At the end of the day, I think ‘groove’ is only one word that one might use for trying to understand a phenomenon that’s multifaceted and requires a fair amount of explanation,” he says.

One thing he likes about “groove,” though, is that it’s easy for people to understand.

“It’s important to connect with constructs that people out there in the world identify with,” he says. “And so it’s important then to use language or labels for things that more or less people know what you’re talking about.”

MORE AUDIO from TRBQ:

Subscribe the to the TRBQ podcast on iTunes.

Listen to the TRBQ podcast on Stitcher.

Follow TRBQ on SoundCloud.

does anyone know if there are any sons of thunder recordings?

Vince, we aren’t aware of any commercial recordings by the Sons of Thunder.

that is a real shame. but thanks for your reply.