Storytelling is an integral part of human culture. It teaches, enlightens and connects.

But according to author and playwright Anne Bogart, it can also be dangerous.

Bogart just released a book called “What’s the Story: Essays about Art, Theater and Storytelling.” She’s also the artistic director of SITI Company, a New York-based theater company.

Bogart believes stories have the potential to distract and deceive—yet she devotes her life to telling them.

Part of her aim, she says, is to tell stories in a different way.

“I think that there are two ways you can tell a story,” she says.

One of them is the Steven Spielberg way.

“I think the intention is for every person watching to feel the same thing,” Bogart says.

Bogart is not impressed by a mere tugging of the heartstrings.

“I’m not a fan of Spielberg,” she says.

She says it’s easy to make her cry.

“I cry at advertisements,” she says “You have a little boy and a dog who have been separated for a month and they run across a field, I burst into tears. But that’s actually cheap.”

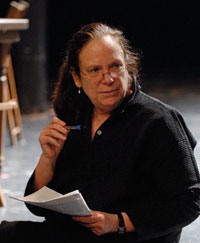

Anne Bogart is the co-founder and co-artistic director of SITI Company in New York. (Photo: Michael Brosilow)

The other way to tell a story, Bogart says, is to create moments in which each person in the audience feels something different.

“Much, much trickier,” she says. “Requires more responsibility.”

Bogart calls the first method of storytelling “fascistic art.” Her definition is “a story that has everybody feeling the same thing.”

“I say fascistic and I mean it literally,” she says. “The role of fascist art was to make one feel small and the same. And the role of humanist art, I would just make up a name, is for everyone to feel that they take up a lot of space and that they have an imaginative and associative part to play.”

This, according to Bogart, is the way to tell stories that are empowering rather than dangerous.

“Participation is key to telling a story that does not simply distract, but actually helps live better,” she says.

To sum up her artistic mission, Bogart quotes the pianist Alfred Brendel.

“He said that when he gets in concert to the end of a sonata, just before the last chord, he lifts his hands in concert and silently asks the audience how long he can wait until he plays the final chord,” Bogart says.

That relationship is the key that Bogart says will keep her in theater forever.

“The theater is mostly mimetic, meaning it is embodied,” she says. “If you’re watching a play, your mirror neurons are actually going wild and doing the same thing as the actors are doing, and your action as an audience is to restrain yourself from doing.”

Bogart says this is what sets the theater apart from other art forms, such as film. In theater, she says, the audience is acting with the actors.

“That’s a very active relationship that story can provoke,” she says. “So I think story is a method to create more aliveness rather than less.”

This aliveness is in direct opposition with what Bogart calls the addiction of our time: the “ping” addiction to electronic devices.

“A story demands more from a human being,” she says. “Stories are beautiful little mini-worlds that do require sustained attention and empathy, which is something we seem to be suffering in its lack.”

Rather than being a distraction, Bogart says storytelling may present a solution.

“Perhaps it is an antidote,” she says.

There is a dark side to storytelling, though.

“Stories are super dangerous, and I think it’s why most of my life I resisted them,” Bogart says. “And yet … stories are a tool. So the question is how can you be responsible with stories, and can you find room for discourse inside of stories?”

Bogart acknowledges all of the dangers.

She uses words like “powerful” and “seductive,” saying stories have the potential to become “fascistic” and to be used as propaganda.

“And yet in the theater, in my business, we are in the business of transporting stories through time,” she says.

Bogart says stories that deal with universal human struggles are the ones that live on.

“The great Greek plays, for example, still exist because we’re still hubristic and the stories are about us dealing with hubris,” she says. “So yes, stories are dangerous but also stories are necessary.”

MORE AUDIO from TRBQ:

Subscribe the to the TRBQ podcast on iTunes.

Listen to the TRBQ podcast on Stitcher.

Follow TRBQ on SoundCloud.

Great stuff!! I first heard these on NPR but couldn’t find the podcast on the one in which people wouldn’t change their minds when presented with the facts because of the impression the story left. Could you give me that link, too?

Glad you liked the podcast, George.

The discussion you allude to is in the radio special, “What’s Your Story?” Check out that program — and all TRBQ audio — here:

http://trbq.org/listen/

why is the text not a transcript? I would really love a transcript of this piece.

Thanks so much for listening, Noel. We’ve talked about it putting up transcripts. As it is now, the bulk of the podcast does appear in the print version. We opted for trying to make it a bit more reader-friendly online, though.

…there’s a print version?? please to provide me a link or info on how I can get my grimy mitts on said print version. thanks!!

The print version is right above — it’s the text in this very post. If you’d like a hard copy to print, you can find a PDF of the story here:

http://trbq.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/TRBQ_podcast10_bogart_print.pdf

One great danger of stories, which this podcast does not mention, is the danger of stories in science. Today, more and more, scientist conceive of their work as ‘storytelling’. They publish ‘stories’, carefully woven accounts of how they made discoveries. Journals and readers want to read about stories. However, great discoveries in science are rarely part of great stories; more often than not, data are not interesting. What I see happening now, especially in neuroscience, is the fitting of data to a narrative, and this frightens me. Consider even the examples of science used in this podcast–“the same regions of your brain light up when reading a part of a story as when performing that same action”! Wow! A story-truth or a real truth? Who cares….its a great story….