Why do people share? In this episode we hear from Yochai Benkler about his research into people who write Wikipedia articles, and we meet Sam Harnett who moonlights giving people rides — and recording their stories.

Any given day, in any given place, someone is giving away something of value. Money, time, expertise.

Some even give their knowledge away. Millions of people spend hours writing entries and checking facts for Wikipedia about black holes, Bolivia and Justin Bieber—and that’s just the B’s.

And they do it for nothing.

In fact, sometimes people are more likely to do something for free than for money.

Yochai Benkler is a professor at Harvard Law School and the co-director of the Berkman Center for Internet and Society. He studies how people share and cooperate.

“Let’s imagine you volunteer to clean up the park,” Benkler says. “It’s a way for you tell yourself, ‘I’m a good person.’ It’s a way for you to tell your neighbors, ‘I’m a good person.’”

Now imagine that the city decides to pay everyone who helps $50.

“Suddenly you scratch your head,” he says. “And you say, ‘Well if I go, am I really doing it for the $50 or am I doing it because I’m a good person?’”

Yochai Benkler is co-director of the Berkman Center for Internet & Society at Harvard.

(Photo: Joi Ito)

Benkler says at this point people will often find a different, unambiguously good activity to achieve the sense that they are a good person.

The same dynamic is at play when you start getting paid for a hobby, like music or painting.

“There are ways in which adding money doesn’t necessarily destroy the pleasure and the quality of the interaction, but it requires a lot of care,” Benkler says. “We have a complicated relationship with money. To some extent we need it, to some extent we need to be outside of it.”

When it comes to information sharing, like open-source software and Wikipedia, public recognition can also be a factor. Benkler says different people respond to different motivations for this kind of sharing.

“Some really seem to care and be responsive more to social recognitions,” he says. “Others seem as though they couldn’t care less. … Others are going to be willing to give for no reason at all, simply because it’s the right thing.”

Benkler says whatever the flaws and limitations of something like Wikipedia, it’s important to remember that 13 years ago, anyone who predicted the extent of its success would have been laughed out of the room.

“Wikipedia is essentially an impossibility,” he says. “It is something that the economic models that were dominant from the late ’50s until the last decade simply predict wouldn’t exist.”

But it does exist. And more. Benkler calls it “an enormously important part of 21st century life.”

Benkler says this teaches us something important about society.

“People can manage their affairs without necessarily the force of law, without the authority of contract, without the forcing power of property,” he says, “but rather by getting together and negotiating their relationships.”

That is just the sort of thing that Sam Harnett is trying to do.

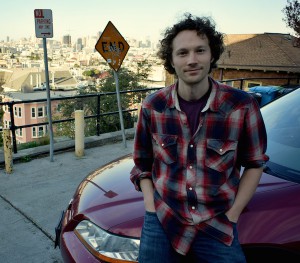

During the day, Harnett is a reporter at public radio station KQED in San Francisco. At night, he moonlights giving people rides.

Harnett is signed up with a rideshare company. He uses his own car and people request rides via smartphone.

Harnett is a little different from most drivers, though. He brings along his audio gear so he can interview his passengers. Then he turns their stories into a podcast called “Driving with Strangers.”

“They get in the car and I explain to them the show, hand them a couple index cards of questions, and then they pick the questions they want to answer and I record them,” he says.

Harnett’s questions vary.

“Some of them are pretty innocuous,” he says. “Like, ‘Have you ever had an odd job?’”

Even that one gets some interesting responses.

He once had three people in his car who worked in a local dungeon as dominatrices. Another woman worked in a bong factory.

Other questions, Harnett says, are a little deeper. Questions like, “Have you ever uncovered a secret?” or “Have you ever had a near-death experience?”

“I was attacked by somebody close to me very, very unexpectedly and left for dead,” one passenger says.

“I didn’t remember anything until coming to in the ambulance,” says another.

Still a third recounts a harrowing tale: “The entire time the guy had the gun pressed against the back of my head as they were duct taping my hands and feet.”

Harnett says he believes people tell him these intimate stories because, basically, he’s just a guy giving them a lift.

Scholars say people’s relationships change if they exchange money. They say paying someone “increases social distance.” When no money changes hands, there’s less social distance.

That’s what Harnett thinks, too.

“I feel like in a regular cab, the interaction is so much more of a business transaction,” he says. “People get into the back seat. There’s cash that’s exchanged directly.”

In the rideshare model, Harnett says, the money is handled on a smartphone and the passenger sits in front. In fact, the people who participate in this program are almost expected to have a conversation.

“I was thinking at first, ‘Wow, if I got into a cab and they kind of put me on the spot and asked me to tell a story I don’t know if I would do it,’” Harnett says.

He was worried his first passenger would ask to get out at the next corner.

“But it ended up being the opposite,” Harnett says. “People would get in and I feel like it was almost a relief to get these questions as sort of an icebreaker, as opposed to having to strike up a conversation.”

Get Podcast 3 — The joy is in the giving

Read more about sharing on TRBQ.

MORE AUDIO from TRBQ:

Subscribe the to the TRBQ podcast on iTunes.

Listen to the TRBQ podcast on Stitcher.

Follow TRBQ on SoundCloud.

I disagree with the content that people need to consider whether or not they are good people once they are getting paid to be good. On contemplation I think if I start getting paid for doing something I start wondering if I actually want to do it. For this that are typically volunteer the pay usually isn’t worth the effort.